The African Union Startup Model Law Framework at a Glance

Tags

The African Union (AU) Model Laws are a set of template frameworks designed to ensure uniformity and guide member states in formulating governance strategies across various sectors, such as access to information, medical products, or technology. Among these is the Startup Model Law Framework, released in July 2024, which provides a comprehensive strategy for fostering a thriving startup ecosystem in Africa. It encourages member states to develop national startup strategies aligned with this continental vision.

Having a unified continental strategy for startup enablement and regulation is crucial, especially as startups often expand across multiple national jurisdictions over time. Recognizing this, the framework builds on existing startup laws in countries like Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Tunisia, and Togo. These nations have seen notable success following the enactment of their respective Startup Acts.

For example, after ratifying its Startup Act in 2018, Tunisia experienced a 72% increase in startup funding between 2019 and 2021, along with a 75% rise in the number of businesses receiving the official “startup” label. Similarly, Senegal, after passing its Startup Act in 2019, saw startups raise approximately USD 353 million. The reasoning behind this success is clear: investors tend to have greater confidence when there are well-defined, enforceable legal frameworks that protect their investments.

Beyond promoting uniformity, the Startup Model Law Framework aims to motivate countries without a startup strategy to develop one. A continent-wide approach to startup governance encourages knowledge sharing among member states and aligns efforts toward equitable partnerships and funding. Currently, most startup funding is concentrated in four major markets—Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt—which together receive over 70% of Africa’s startup funding each year.

The framework also builds on earlier governance efforts in the digital economy and innovation sectors, such as the AU E-commerce Strategy, the AU Data Policy Framework, the Malabo Convention (AU Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Sharing), the Smart Africa Initiative, the AU Free Movement of Persons Protocol, and the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). Several of these frameworks, including the AU Interoperability Framework for Digital ID, the Data Policy Framework, the AfCFTA’s Digital Trade Protocol, and the Smart Africa Initiative—which seeks to create a single digital market for Africa—already incorporate cross-border interoperability and common standards for digital businesses.

However, Africa still has the lowest intra-continental trade globally, due to challenges such as regulatory ambiguity, policy fragmentation, high cross-border transaction costs, and restrictions on labor mobility. One of the key goals of the startup framework is to address these challenges by promoting labor mobility, advocating for multilateral profit-sharing frameworks over unilateral digital services taxes (DST), and encouraging the establishment of One-Stop Shop (OSS) platforms for startup formation, licensing, and regulatory compliance. The African Tax Administration Forum provides a useful operational framework to support these goals.

Structure of the Framework

The framework is based on five core principles: inclusivity, free movement of labor, a predictable policy landscape, evidence-based policymaking, and the recognition of existing policy frameworks.

It outlines seven key areas of strategy and policy:

Governance and Regulation

The framework emphasises the importance of startup governance. Different countries have varying approaches. Tunisia and Nigeria use a hybrid model, where multiple government agencies oversee different aspects of startup governance. In contrast, Togo has streamlined its process, simplifying business registration. However, many African countries do not have dedicated startup agencies. This section recommends the establishment of such agencies under innovation and digital economy ministries to ensure efficient governance.

Regional and Continental Institutional Support

This section focuses on enhancing cooperation between member states and fostering a continental culture of innovation. It highlights the need for stronger collaboration, such as establishing a permanent secretariat for the African Startup Conference and exploring the creation of an Africa-wide government startup agency.

Startup Formation

Next, the framework outlines the criteria for defining organizations as startups. Given the long-standing ambiguity around what qualifies as a startup—such as the debate over whether all small businesses fit this category—the framework provides a clear set of criteria. Startups are categorized as businesses that prioritize innovation, are capital-intensive, engage in R&D activities, offer technology-driven products or services, and generate substantial intellectual property assets.

Taxation

The taxation section explores how tax policies can support startups. It advocates for favorable tax incentives, different tax vehicles, and using tax instruments to encourage the formal incorporation of women-led startups. Tax policies are viewed as essential tools for creating a more supportive environment for emerging businesses.

Structural Enablement

This section is perhaps the most comprehensive, focusing on the macroeconomic conditions necessary for startups to thrive. These include funding, insurance, foreign exchange controls, investor-state dispute resolution mechanisms, R&D incentives and more. The framework pays special attention to the funding gap, the most significant challenge facing African startups. It also addresses other barriers, such as cultural challenges and organizational capital, to ensure startups have the structural support they need to succeed.

Regulatory Enablement

Drawing on the AU Data Policy Framework and the Malabo Convention, this section focuses on regulatory measures that facilitate startup growth. It highlights the importance of data protection, cross-border data transfer, and the resolution of competition and intellectual property (IP) issues. The framework addresses the rights and enforcement of IP in the startup sector, ensuring that data-sharing practices are legally protected and competition remains fair.

Education, Innovation and Skills Development

The final section emphasises the importance of fostering a culture of innovation through education and skills development. It encourages member states to integrate digital literacy, business education, and entrepreneurship into formal education curricula, particularly at the tertiary level. The framework also stresses the need to strengthen university research labs and incubator programs and to raise public awareness about legal, financial, and strategic support for informal entrepreneurs. This will help them transition into formal entrepreneurship and contribute to a thriving startup ecosystem.

Overall, the African Union Startup Model Law Framework emphasizes how governments, both regionally and nationally, can create a supportive environment for startups through targeted legislative and policy interventions. It highlights the rise of Startup Acts as the modern equivalent of small business acts, designed to support high-growth, technology-driven businesses, particularly in the digital economy. Currently, at least 35 AU member states have either enacted or are developing startup legislation.

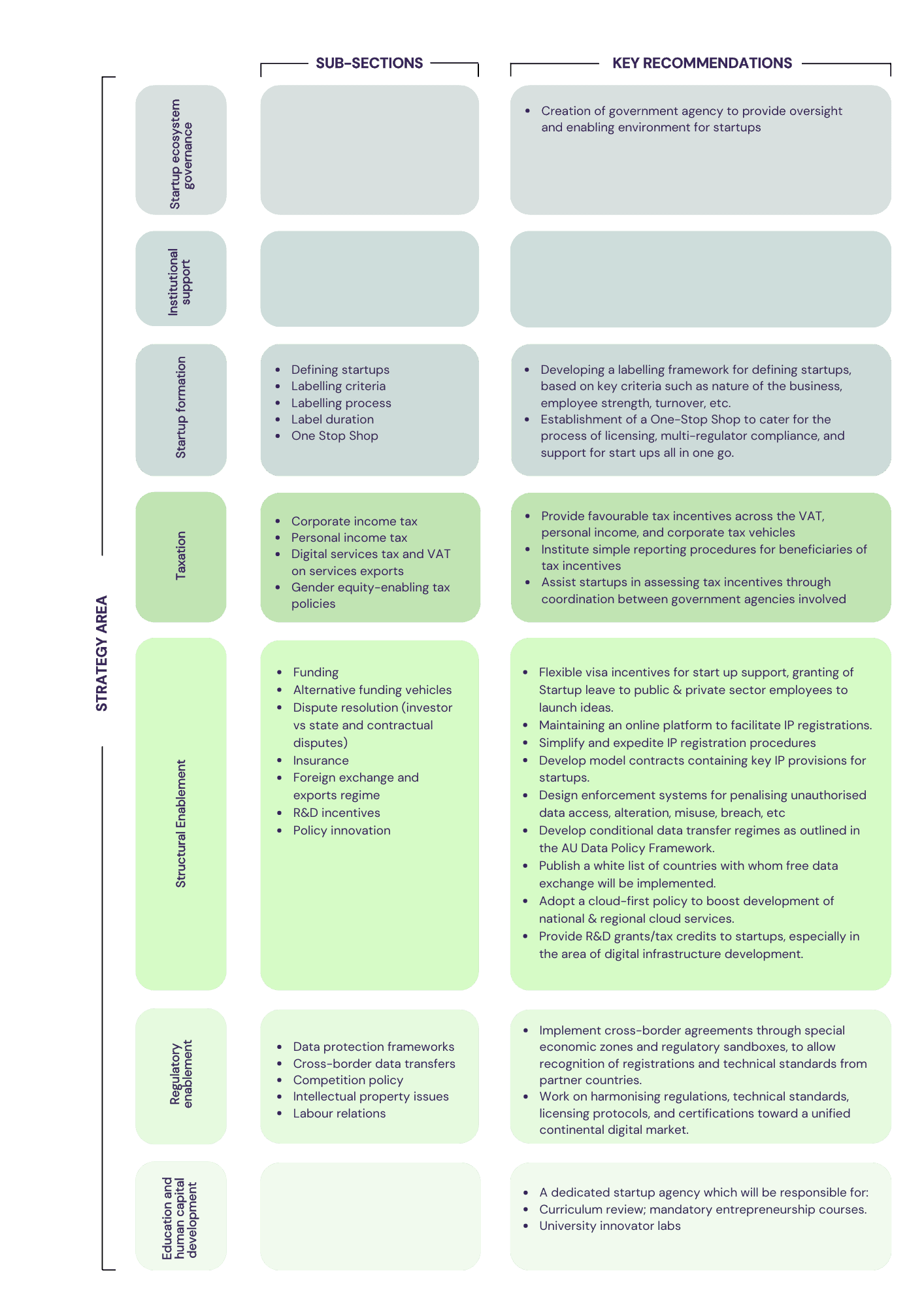

The framework offers several concrete recommendations for these countries, including establishing specific government bodies to oversee the implementation of the law, creating a labeling and identification system to certify businesses that qualify for specific incentives or programs, and introducing tax incentives to reduce the financial burden on startups (see table below for a more detailed list). As the framework notes, not all supportive measures for startups require formal legislation; softer policy tools are also widely used, such as digital economy strategies, financing programs, and business support initiatives.

Summary of the framework strategy areas and their respective policy recommendations

Missing Pieces

While the Startup Model Law Framework is comprehensive and detailed, it misses an opportunity to address a few emerging concerns in greater depth.

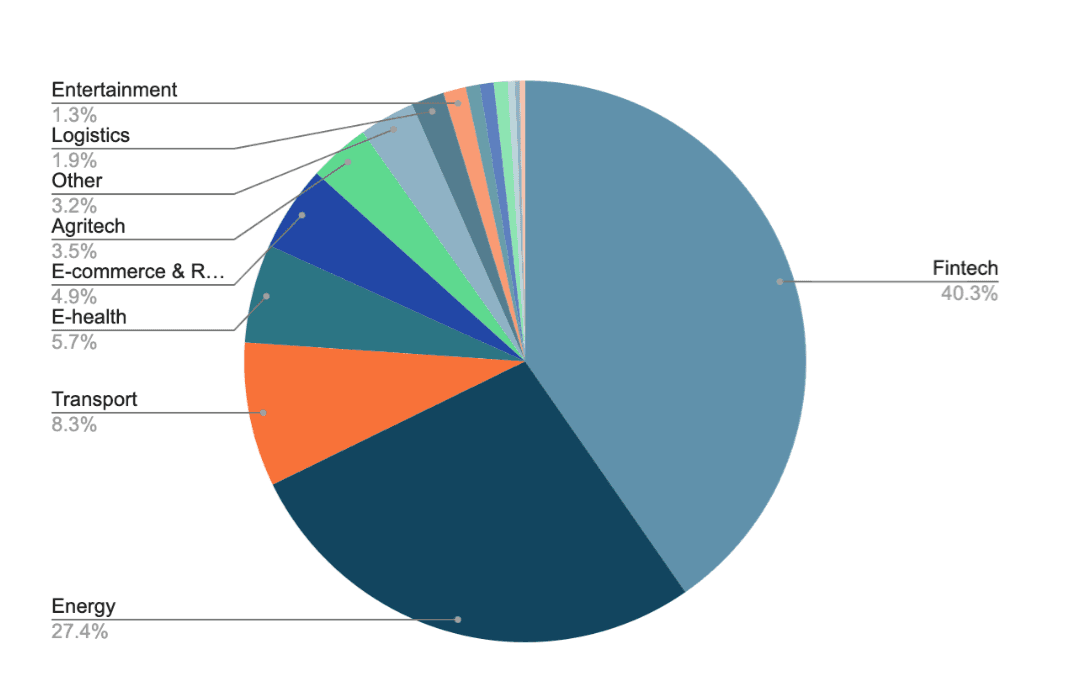

First, there is little discussion on the sectoral landscape as a strategic area for startup enablement. Although the framework briefly mentions the dominance of fintech in Africa’s startup scene, it does not delve into the importance of fostering growth in other sectors where significant innovations are occurring but remain underfunded due to investor preferences and policy priorities. For example, nearly half of the funding for African startups each year goes to fintech businesses (see figure below). While fintech has dominated the conversation in recent years, the real potential for stimulating broader growth lies in traditional value-creating sectors such as agriculture, education, energy, and health. With the exception of energy, these sectors continue to receive disproportionately low funding relative to the capital needed to scale. Stimulating the supply of capital through targeted policies is essential to unlocking their potential.

Source: Author, based on The African Tech Startups Funding Report, 2023.

Strengthening State Capacities

Another area that could have enhanced the framework is a discussion on how to strengthen the capacity of states with weaker startup ecosystems. For instance, with over 70% of African startup funding going to the “big four” markets—Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt—the framework could have provided a blueprint for establishing equitable funding mechanisms and strategies for other states to leverage the success of these dominant markets. However, this may fall beyond the scope of a model law, as strategies for fostering competitiveness and attracting capital can vary significantly from one state to another.

Looking ahead, a major obstacle to realizing the framework’s ambitions is the limited policy uptake or ownership at national and subnational levels—a common challenge with AU or regionally developed policies and frameworks. To prevent the framework from becoming just another “governance document” with limited impact, it would benefit from an implementation plan. Such a plan should outline measurable milestones, actionable steps for each state, and include short-, mid-, and long-term evaluations of member states’ progress in adopting the framework.

Conclusion

The Startup Model Law Framework is a significant step forward in building Africa’s AI ecosystem, which is predominantly made up of startups. Developing a vibrant and inclusive startup ecosystem is one of the 15 key recommendations of the AU Continental AI Strategy, published in August 2024. Many national AI strategies also prioritize startups. For instance, Nigeria’s AI strategy, released in August 2024, focuses on supporting a network of successful AI startups that drive innovation and contribute to economic growth. This aligns with the AU’s continental strategy for promoting AI startups as engines of growth in Africa and creating a critical mass of innovators who will position the continent competitively in the global AI market. Consequently, implementing the Startup Model Law Framework is essential to advancing equitable AI development across Africa.

Authors: Ayantola Alayande & Fola Adeleke

Acknowledgement:

This analysis is based on research funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and UK International Development under the AI4D program, as part of the African Observatory on Responsible AI.